My rational mind knows that I am not in danger, but my body refuses to believe it. It retains the memory of traumas I have lived. It starts the sweating, jagged breathing, dry mouth, and trembling hands to warn me. It tries to prepare me and protect me from danger that I know is not there, but that could be.

The worst is when I feel like I can’t swallow. It’s like drowning on land while looking at water. No – the worst is when I avoid being with people, when I don’t go where I want to go, and when I make excuses for my absence because I dread this feeling. Because I fear the fear.

I am like many people who suffer with anxiety in the form of panic disorder or agoraphobia. (Agoraphobia is anxiety about being in places from which immediate escape might be difficult, like on public transport, or where help may not be available, like outside one’s own home.) Like many of them, I am a master of masking, avoiding, deflecting, and camouflaging. Most people who know me would never suspect from my calm demeanour that when we take the lift together, I can’t hear what they’re saying because my panicked heartbeat is drowning them out. That if we go to a movie or a crowded restaurant that I am identifying all of the exits as we chat away merrily.

Those of us with chronic anxiety live not only with its exhausting physical and mental symptoms, but also with the guilt and shame of having a condition that robs us of confidence at work, makes us fade into the background in social situations, and leaves us wracked with regret when it holds us back from travel or parties or important life events for the people we love.

Therapy taught me that my anxiety is part of how I am wired and I that I will probably never be free of it. I am the daughter of anxious people. My parents and grandparents were Ukrainian refugees from World War II. My father fought in the Vietnam War. I was raised by people whose lives were shaped by war, hurt by it, and who understandably viewed the world as a dangerous place. I inherited their hypervigilance. And their fear.

My anxious wiring was then reinforced by the traumas I survived – running from the collapse of the Twin Towers on 9/11. The brutal emergency c-section of my first son and his subsequent illness. A second, more brutal emergency c-section with an overdose of anaesthesia for the birth of my second.

Thankfully, therapy also helped me realise that with anxiety comes a set of skills and attributes that give us, the Anxious, secret strengths that we have carved out of what others might mistake for fragility.

Years spent battling your own mind hones the muscles of empathy and compassion. Willing yourself every day, to get to work, to get on the bus, to take your child to the doctor even though the waiting room makes you want to scream, to wait on a supermarket queue when the walls are closing in, to sit in a work meeting when you can’t find enough air, to do these daily tasks that most people never even think about, builds a core of resilience, of steadfast persistence and determination.

The strength that comes from living every day struggling against a rogue nervous system always dialled up to high alert is why we — the highly strung, the panicky, the neurotic – are quick and able to respond during real crises. I’ll give you an example. I have two energetic young sons with ADHD who also struggled with asthma in toddlerhood. They are two

tornadoes dancing around each other, physical and fearless. I have had to run through the doors of A & E countless times with a crying, injured boy in my arms, or one who couldn’t find his breath, even though the windowless, fluorescent lit rooms and corridors of hospitals make me involuntarily tearful the instant I step inside. But when my babies need me, my hypervigilant nature reveals its strength. I am calm, clear headed, reassuring to my children. I am a mother, so I silence the fear and the panic recedes when I am called upon to make everything all right.

During this uncertain time of the pandemic, political upheaval, and social isolation, the Anxious know how to comfort those who are afraid because we know fear very well. We know how to support the lonely because we know what it’s like to suffer alone. We thrive on solving a real crisis in concrete ways — organising, donating, communicating – because we have always been prepared to take action after years of battling the invisible, often imaginary, daily crisis in our minds.

The rest of the world was vibrating on our frequency during the pandemic, many people experiencing true anxiety for the first time. Stories emerged about many people with anxiety experiencing a decrease in symptoms. This has happened before. Allen Shawn, author of Wish I Could Be There and Scott Stossel, author of My Age of Anxiety, both point out documented instances of people with known neuroses, anxiety, and agoraphobia performing acts of heroism during the Second World War. When facing real danger, their symptoms dissipated, and they rose to meet it.

I have always kept my anxiety and irrational fears well hidden from my children. One of my biggest fears has always been that they would model my behaviour and become burdened by anxiety as well. But with time they have started to notice Mummy’s “quirks.” They are old enough now to see the cracks in my veneer.

Recently, our family was faced with a POD, a tiny, enclosed, robotic vehicle from my worst nightmares that would transport us to the long stay car park at Heathrow. My sons were delighted with this car from the future but I couldn’t step inside. “I can’t do this, pick me up somewhere else,” I pleaded with my husband. But there was no choice, no way to escape,

so I got in, clutched my seat, shut my eyes, and barely spoke. I could not disguise how hard it was for me in front of the children.

Was I teaching them how to be anxious? No, I choose to think that this too was a lesson in strength. They saw the strength it takes a person to be vulnerable, to admit that they’re scared, and to ask for help. They saw me confront a fear, head on. They saw my anxiety on display, yes, but they also saw my strength.

– Ilona Bannister

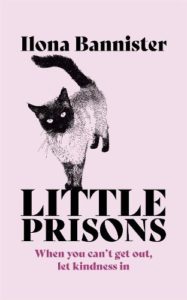

Little Prisons by Ilona Bannister is out now, published by John Murray Press.

More midlife health

View All

‘I looked like a success but I was too numb to enjoy anything’

Helen Barnes on how she gave up traditional notions of success, concentrated on her family and discovered the joy of reinventing herself.

How learning to surf at 50-plus changed me

Danielle Cass began surfing age 50 plus and turned from invisible to strong and beautiful

Catherine Mayer on the physicality of grief

Catherine Mayer’s beloved husband Andy died at the beginning of the pandemic, only weeks after her stepfather. Since then she and her mother have been sharing their bereavement journey together, culminating in writing Good Grief, a book which is searing about loss but optimistic on how to re-embrace life. Here is an edited extract of a brand-new chapter about how grief affects body as well as soul.