Growing up in Luton, a mixed-race girl adopted by a white family, living in a predominantly white community, nobody looked like me. Back then, I didn’t have any role models or representation of successful female business owners, and certainly not any who were black or brown. My dad had run his own business for a short time, but it sadly ended disastrously with unhappy consequences for my family, which unsurprisingly led to my parents encouraging me to seek ‘job for life’ employment where I would be safe, secure, and ideally recession-proof. They were overjoyed when I started working for the Government Communications Service, a specialist body of professionals, within the then-Labour government, under Tony Blair’s leadership. As a marketing and campaigns lead these were the heady days of big advertising spends, visible work, and a high level of meaning to my career.

Fast forward almost 20 years, and as I approached my 40th birthday, I increasingly couldn’t shake the feeling that something was missing from my life. Professionally, I’d been having an exciting time. In 2008 my now-husband Jon and I relocated to the UAE. Whilst there I began working in film and media (but still with a strong impact and cause-driven leaning). I was travelling the world collaborating with influential organisations and people such as the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Malala and Ziauddin Yousafzai, and Harvard University, to name drop a few. During my time overseas I set up my own consultancy (employee count: one), which gave me a level of autonomy and freedom I really enjoyed.

Something had to change

The good news…..and the bad news

We did a pretty good job of that, and were thrilled to see the tell-tale double lines on the pregnancy test a week after my 40th birthday. A final, treasured birthday gift. As my pregnancy developed and I started getting used to my new mama-to-be persona, a strange thing happened. My business disappeared overnight. A long-standing contract came to an end, as already mutually agreed, but whereas I assumed something would easily come and take its place, nothing happened. I was doing all the right things, pounding the pavement, arranging meetings with potential clients, but to no avail. As the months continued, I wondered if I had accidentally made a non-fairy-tale trade-off with a Disney-style villain along the lines of “Yes my pretty, you can have your baby, and I’ll have your livelihood in return.”

In all, I didn’t work for two years, including the six months I took off for maternity. That period was the best of times (I baked and delivered my gorgeous girl) and the worst of times (I lost my professional identity and my financial security). It was incredibly scary, and I felt quite lost.

Trust the process

It was during this time, I came across a transformational coach named Peter Opperman. His 8-week incubator is designed for participants to “meet their future self and learn how to prototype your dreams into reality”. Rooted in neuroscience and quantum physics, a daily meditation practice is a key cornerstone of the programme, alongside deep inner-child and shadow work exploration.

As a recovering perfectionist and control freak, I was putting a lot of pressure on myself to get all of the answers I longed for, however Peter advised me to simply focus on making the daily morning meditation a habit (yes, even with a six-month old baby) and to follow the breadcrumbs of what came up, or along. Trust the process in other words.

Learning from my inner child

So, I did, and as I went on this journey with around 10 others from across the world (predominantly the US and Canada), I started to get really curious about some of the insights and questions which arose. When tapping into our inner child, why was it that so many of us (if not all) were still carrying around so much unresolved psychological trauma from our childhoods? Why was it, I soberly realised, that I had spent the past twenty years of my life working hard to come to terms with the first twenty years of my life?

Back to the beginning

Flashbacks of my younger self and some of the troubling experiences I had gone through as a child came

Things went from bad to worse, and eventually I was taken into emergency foster care aged ten months. I was lucky that my foster carers became my adopted family. Having arrived in the middle of a snowy January night, I never left. And despite being enveloped in love by my new parents and sisters, growing up was really challenging. I remember quite clearly the first time I looked in the mirror and saw myself as brown, and different to my family. I would have been four or five, alone in my sister’s bedroom, when something that previously wasn’t there took root in my brain and has never left.

Different, and not in a good way

Not only did my little mind understand that I was different, but I also somehow automatically knew that this difference wasn’t good. Those feelings of not fitting in, of being ‘other’, extended outside of my home. Surrounded by a white community, I looked different, felt different, and had no real understanding of where I came from, or where I belonged. They were lonely and confusing times.

When I started secondary school there were so many things that seemed to me to be wrong with me: adopted, brown, frizzy hair, the way I spoke, my bookish-nerdy ways, our family being in the Salvation Army, even the fact I played the cornet. None of this was remotely cool, or socially acceptable. I stuck out like a sore thumb whether innocently walking round with my mum and dad on parents evening, at church, or out ‘in the wild’.

If a group of us from school were spotted down the chippy at lunchtime (a detention-worthy offence), I would always get be the one to get caught because I was the brown one, and easily identified. Significant bullying (not racially motivated) followed around the time I hit puberty, which only added further layers of insecurity, low self-esteem, and the reinforcement of the belief that I simply wasn’t good enough.

Coping with childhood

Aged 40, and now a mother myself, as I looked at the gorgeous baby in my arms, I knew that I didn’t want her to experience any of the difficult feelings that I had, whilst being old and wise enough to finally understand that none of us seem to get out of childhood unscathed. The stories and characters might be different, but the myriad feelings of inadequacy, shame, guilt, pain, abandonment, rejection, and more, and more, are universal.

The questions continued to whirr in my mind: why wasn’t more being done to ‘interrupt’ these experiences as they happened, and prevent emotional scars from forming whilst still in childhood? Why weren’t we providing children with tools and coping mechanisms to carry with them on the rollercoaster of growing up?

Grim statistics

I started looking at the statistics. They made grim reading. We are in the midst of a global children’s mental health crisis, with no clear solution from leadership in sight. UNICEF have said that the impacts of the pandemic will be felt particularly strongly among children and young people. In the UK, one in six children are diagnosed with a probable mental health disorder, with only one third of referred children being able to access support from the NHS. It may take many years for us to truly understand the full consequences of Covid19’s disruption to young lives, but already we are seeing unprecedented numbers of children absent from school. The Centre for Social Justice has identified almost two million so called ‘ghost children’ and predicts these numbers will continue to rise for many years ahead as the babies, toddlers, and pre-schoolers of the pandemic era enter an education system and environment that they haven’t been adequately socialised for.

This was the problem I wanted to solve

As I immersed myself in these studies, thought about little Rebekah and all the things she went through, and then looked again at my little baby, a lightbulb went off. This was the thing I was here to do. This was the problem I wanted to solve.

And that’s how my journey in life led me to develop my idea for Happy Marlo, a children’s wellbeing platform with the mission to emotionally empower young children through fun and accessible wellness tools rooted in breath work, emotional freedom technique (aka tapping), and sound healing.

The world I want to create for children

That’s when it starts to get really exciting. What types of purposeful adults might these children become? And if they choose to go on to have their own children, what kinds of parents might they become? Armed with mindful practices, empathy, and understanding, could we finally have an opportunity to break down the cycles of generational trauma once and for all?

That’s the mission we’re following at Happy Marlo, and whilst we’re just getting started, we can’t wait to play our part in making this particular dream become a reality. Our future depends on it.

Explore Rebekah’s website, Happy Marlo HERE

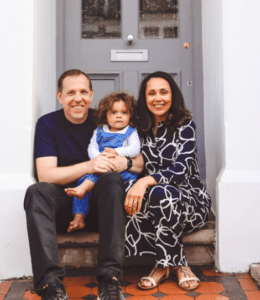

By Rebekah Clark