My father Kurt Schindler was handsome, persuasive, funny and charming. He was a raconteur, full of anecdotes of our lost family business and our illustrious relations who supposedly ranged from Franz Kafka to Oskar Schindler to Hitler’s Jewish doctor, Dr Bloch — the only Jew in the German Reich who enjoyed Hitler’s personal protection. The only problem was I never knew whether to believe him.

A fraught relationship with my father

As a small child I adored my father but as I grew older I also realised that he had little in the way of a moral compass. He was adrift in his own confused sea of recrimination and litigation. Kurt portrayed himself as having suffered great injustices, not only as a Jewish victim of the Holocaust but also at the hands of his own family, with whom he had fallen out. My father’s goal was to right all those wrongs regardless of the cost or prospects of success. He thought nothing of pursuing and defending hopeless restitution litigation to reclaim assets he thought had been taken from him. In the process he ran up debts he could never realistically pay. He always maintained he had “no choice”: His family empire had been lost and he wanted to restore the wealth and luxury of those pre-war years. The means always justified the ends for him. Our family life was defined by his obsession with litigation.

No deathbed reconciliations

Kurt died in May 2017 at the age of 91. I chose not to be there when he died. I had a fractious, difficult relationship with him all my adult life and I did not believe in deathbed reconciliations. I kept Kurt at arm’s length, convincing myself that I had to protect my family from him and focus on my own work as a lawyer. Now I see my absence in his last days and hours as a mistake: a cowardly act and a failure to grapple with that difficult relationship. I had turned my face to the future and shut the door to the past. Or so I thought. As the condolence messages arrived from friends and colleagues, I felt numb and then angry. I mourned the father I had never had.

It fell to me and my sister and our two husbands to sort through what Kurt had left behind in the small cottage where he died. He had lived there alone with an ever changing cast of carers after our mother’s death 11 months’ earlier. The cottage was in chaos. Papers were piled up in every corner: the spare bedroom, his bedroom, the small sitting room and dining room. We opened the doors of the double garage and faced floor to ceiling cardboard boxes crammed with papers from failed business ventures and court cases from around the world. Our father had funded his thirst for litigation by setting up and running commodity trading companies, which regularly failed. We had a turbulent childhood: at times we rode in expensive cars and attended up-market private schools; at others we were evicted from our homes, forced to flee Kurt’s creditors and hide from bailiffs.

Shocking discoveries

In the cottage, we started by trying to be systematic and reading the pages we were sifting. By the end we were tearing through boxes in a frenzy of paper skimming. Some documents were mundane: slips of paper with the arrival times of trains for our visits from London written in blue biro; others were shocking: detailed reports from private detectives who had been hired by our father to spy on us.

Kurt had loved us deeply and obsessively. He had sought to control his two daughters and when my younger sister had brought home a boyfriend he disapproved of he commissioned a detective to stake out the boyfriend’s family business and home. I remembered the rows about this particular boyfriend and how Kurt had inflamed those conversations by dropping hot coals of facts into them: “You cannot possible think he is suitable for your sister; you have not seen his mother.”

We were angry and shocked. But there was more: piles and piles of Nazi era documents festooned with swastikas; letters ending with the peremptory sign off: Heil Hitler. Papers that related to the café, the villa and distillery business which had been stolen from Kurt’s family by the Nazis. These were losses which Kurt never forgave and drove him to pursue ever more far-fetched legal claims with ever diminishing chances of success. Kurt was a compulsive gambler: He gambled with our stability and happiness. In one unusually perceptive moment, my father conceded that he liked “living on the edge”. It never occurred to him to ask whether we wanted to live there with him.

After two exhausting, filthy days of sifting documents, we packed up the papers we thought we should keep, scooped up thirteen battered old photo albums and left the cottage to its fate. Kurt’s estate was insolvent. There was no point taking out probate.

Discovering lives through old photos

When we returned to London, the papers ended up in several trunks in our basement. I could not face looking at them. The photo albums were a different matter. As I leafed through them I suddenly wanted to know more about the people I could see in them. I found extraordinary pictures of a coffee house which had been at the centre of the Innsbruck’s social life. I discovered young men in crisp uniform on the cusp of the First World War, posing before setting out to fight for Kaiser Franz Josef; women in long dresses and bonnets astride toboggans preparing to hurtle down snowy slopes. I was gripped by a desire to know who they were and what had happened to them. And Kurt was no longer there to ask.

I started to research my Austrian family, spending weekends and evenings trying to piece together the identity of the people in the photos. Some things were accessible online; others required me to write off to archives and museums in Austria to ask for copies of files held by them. The past started to come into focus and I could name the people in the photos and I wanted to write down their story.

Trying to understand my father after his death

It was an attempt to understand my father retrospectively: to sort fact from fiction and understand my own history and with it the history of Austria as it emerged from the Austro Hungarian empire and slid into the hands of the Nazis. My research led me to reconnect with family members with whom my father had fallen out and I rediscovered whole branches of my family whose existence I had known nothing about. The initial approach to these people was rather telling: Some reacted with hostility and suspicion variously describing Kurt as “a thief” and a “crook”. It became my mission to try and reunite a family that had been scattered by war and feuding.

A project that started private and became public

As the project gathered momentum, I started to feel out of my depth. I am a trustee of a wonderful creative writing charity: the Arvon Foundation. It owns three rural houses with literary connections. I booked myself on one of its weeklong life writing courses in the spring of 2018. As a lawyer I have to draft statements and write letters for others. Writing about my own family was much harder and more painful. As my fingers touched the keyboard, words streamed onto the screen and the tears flowed. Yet I found the writing calmed the rage and disappointment I felt. It became self-prescribed bereavement counselling, bringing some clarity and healing into the past.

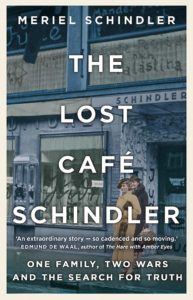

Meriel Schindler’s family memoir The Lost Café Schindler is published by Hodder & Stoughton on 6 May 2021 priced at £20.

The Arvon Foundation: https://www.arvon.org/

family

View All

Saying goodbye to the family home

After the pandemic, Jane Green and her husband were left with an empty family home. Here’s how she moved on

Picture: Adrian Sherratt

Sibling advocacy: How I learned to speak up for my brother

Speaking up for disabled siblings is an important role that women in midlife assume more and more often. Kate Spicer tells her story

I’m so glad lockdown is over – it nearly broke me

Staying home with your nearest and dearest may have turbo-charged some relationships, but for me it’s pushed the limits

The joy of lockdown with teenagers (really)

A year of lockdown with children was difficult — but it provided unexpected benefits for Clover Stroud and her teenager