Among the many unsavoury lessons we learned from the recent Johnny Depp v Amber Heard trial, one of the biggest takeaways was that the most unforgiveable quality in a woman is being unlikeable. It’s a criticism writers often hear in relation to female characters, as if readers (let’s be honest, women readers) are only capable of caring about a character they’d like to be friends with.

This is an absurdly reductive way of looking at literature, and yet it’s remarkably persistent. I often think of the scene in Todd Field’s 2006 film Little Children, where Kate Winslet’s character, an academic who has given up her career to raise her daughter, joins a suburban book group and mounts an impassioned defence of Emma Bovary (the novel Madame Bovary on which the film is based is a nod to Flaubert’s original). One of the judgy moms curls her lip, exchanges a glance with the others, and says, ‘I thought Madame Bovary was a bitch.’

How we feel about women behaving badly

In a way, they’re both right, of course. Emma Bovary behaves terribly, and her behaviour is also understandable; the same is true of Amy Dunne in Gillian Flynn’s multi-million-selling thriller Gone Girl. When the book came out, Flynn was repeatedly accused of misogyny and betraying feminism through her portrayal of Amy, who is often dismissed by those who didn’t like the novel as a psychopath. In response, Flynn said “For me, [feminism is] also the ability to have women who are bad characters … the one thing that really frustrates me is this idea that women are innately good, innately nurturing. In literature, they can be dismissably bad – trampy, vampy, bitchy types – but there’s still a big pushback against the idea that women can be just pragmatically evil, bad and selfish.”

It might be argued that Amy Dunne’s appearance in 2012 paved the way for a new generation of bad girls in fiction and drama, from Killing Eve’s Villanelle to Grace Bernard, the anti-heroine of Bella Mackie’s bestselling debut How To Kill Your Family. But anti-heroines are not quite what people mean when they talk about characters not being ‘likeable’. Anti-heroines are usually larger-than-life, deliciously clever and scheming, and often – like Amy Dunne or Villanelle – young and dangerously sexy. They’re attractive because they’re prepared to take up space in the world; they have agency, even if they use it to act in ways we would never consider or approve of. No, when people talk about female characters being ‘unlikeable’, more often than not they mean women in midlife who are not so much evil as merely tired, embittered, angry, frustrated, impatient (whisper it: menopausal) – all the qualities society doesn’t like to encourage in women.

My favourite unlikeable heroines now

Naturally, these days this is my favourite kind of heroine; I call them “women who’ve had enough of your shit”. I’m thinking of Nora Eldridge, the central character in Claire Messud’s 2013 novel The Woman Upstairs, a thwarted artist in her 40s whose narrative begins, “How angry am I? You don’t want to know.” Nora provoked a raft of articles on the subject of unlikeable women when Messud was asked in an interview if she would personally want to be friends with Nora (the interviewer was clear that she wouldn’t). “If you’re reading to find friends, you’re in deep trouble,” was Messud’s understandably spiky response. “We read to find life, in all its possibilities. The relevant question isn’t ‘Is this a potential friend for me?’ but ‘Is this character alive?’” (She also noted that this question is rarely asked about male characters.)

I spent a decade writing historical crime novels under the deliberately gender-neutral name S.J.Parris, in the first-person voice of a 16th-century ex-monk. I love delving into Tudor history, I’m deeply fond of my narrator, Giordano Bruno (who was a real person; you can find a statue of him in Rome’s Campo dei Fiori), and of course I’m delighted that readers have taken to him, but I found that as I progressed through my 40s there were aspects of my life, and my friends’ lives, that I could not easily explore from the perspective of an Italian man living in the 1580s. So I turned to my other favourite genre – psychological suspense – in order to write about the issues that were daily on my mind: the pressures of motherhood; the disappointments and possibilities of midlife; the fraying of long relationships and friendships. What it means to belong – in a group, a job, a family, a community – or to fear that you don’t.

Do I like my new character Jo Lawless? Hmm

A weekend house party with Oliver’s old mates from university only heightens her sense of being an outsider by virtue of class and education, but when a charismatic young woman unexpectedly joins the party, Jo is perfectly placed to observe as the newcomer’s presence forces open the faultlines between the friends. I was interested in writing about what happens when a group of 40something couples who go back years collides with the novelty of a confident, beautiful woman 20 years younger; how that sexual energy can disturb the status quo. The way the men start unconsciously peacocking for her, while the women instinctively close ranks. The party ends in murder – it’s a crime novel, after all – but I hope not in a way the reader will predict.

Crime fiction and drama has been a good place to find difficult midlife women in recent years. In The Killing’s Sarah Lund, the original and best Nordic Noir heroine, we finally had a female detective who was as catastrophic at relationships and parenting as her male counterparts (though brilliant at her job). I think of Susie Steiner’s wonderful Manon Bradshaw trilogy; Manon is spiky, argumentative and pushes away everyone who gets close to her. Jean Hanff Korelitz, whose literary thrillers I devour in one sitting, specialises in heroines who need to be jolted out of midlife inertia or wilful self-delusion by the most drastic means; her women are flawed, complicated and entirely recognisable.

My current top heroine: Mare of Easttown

My current top “woman who has had enough of your shit” is Mare Sheehan, Kate Winslet’s magnificent character from Mare of Easttown. Mare is a 40something detective dealing with a cantankerous mother, an ex-husband about to remarry, a rebellious teen daughter and her young grandson, the child of Mare’s dead addict son, and that’s on top of solving murders in her deprived community. She’s permanently pissed-off (I mean, you would be), but she’s also brave and loyal and committed. She has a brief dalliance with a handsome writer but doesn’t drop everything for him; it’s on her terms, and she has other priorities.

This is the kind of heroine I want to watch and read about, and also to create, because this is what makes us interesting, especially as we get older. I’m not sure that I’m always likeable (my son would definitely have a view on that); my friends, who I love dearly, are sometimes difficult and argumentative and stubborn and a pain in the ass. We have a fine long catalogue of regrets and frustrations, we’ve all taken some knocks, and we’ve also learned the hard way that it’s not a virtue to try and be liked all the time. Here’s to more ‘unlikeable’ women in fiction and drama; they reveal us to ourselves.

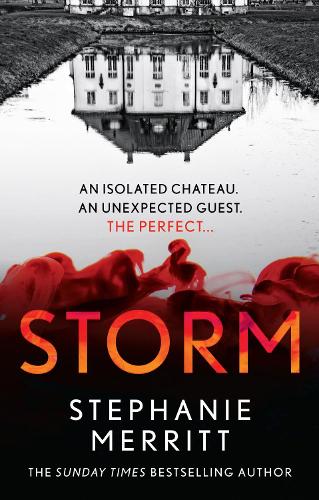

Stephanie Merritt

Storm by Stephanie Merritt is published by HarperCollins June 9th, £14.99

purpose

View All

Queenagers: Why only a fool would ignore midlife women

Dubbed ‘Queenagers’ – with spending power and influence – midlife women are finally becoming the people they were meant to be. So why aren’t people taking more notice?

Picture: Getty Images

Can I stop being resilient now please?

Children, parents, careers and homes — the stuff of midlife comes with one hell of a to-do list and a mandate to just keep going. Must we handle it all?

Picture:Getty Images

Saying no at work is my superpower: how to change your attitude

Anniki Sommerville tells how to make saying no an opportunity for a new career path.

Why we need more midlife women on our screens

The representation of midlife women onscreen is actually declining. To change it, we must work together